Wright County Examiner – October 23, 1997

Glen Buxton, lead guitar for Alice Cooper dies here.

Glen E. Buxton, 49, of Clarion, died Sunday, October 19, 1997 at North Iowa Mercy Medical Center in Mason City. Buxton was well known in rock music circles as lead guitar for Alice Cooper. Buxton was born November 10, 1947 at Akron, Ohio, the son of Thomas J. and Geraldine E. Carlson Buxton. At the age of 14, the family moved to Phoenix, Arizona where he graduated from high school and attended college.

He began his music career in 1964 with a group formed as “Earwigs”. Later they changed their name to “The Nazz” and in the late 60’s to “Alice Cooper” The group broke up in 1974 and Buxton formed a group in Phoenix called “Virgin”. He was lead guitarist with all the groups.

In 1990, Buxton moved to Iowa to help his friend, John Stevenson, farm. He was later with Buxton-Flynn in Minnesota.

Those left to cherish his memory include his fiance, Lorrie J. Miller of Clarion; Parents, Thomas and Geraldine Buxton of Glendale Arizona; one brother, Kenneth of Glendale, Arizona; one sister, Janice Davison and her husband, Bob, of Bullhead City, Arizona; two step-sons, Robert and Michael Busick of Dearborn, Michigan. Services will be held Friday, October 24, at 10 a.m. at Willim Funeral Home in Clarian. Rev. Gary Boen of First Lutheran Church, Clarion, will officiate. Burial will be in Evergreen Cemetery, Clarion. Willim Funeral Home is in charge of arrangements.

***************************

Greg Prato (AllMusic) on Glen’s passing:

A founding member of the Alice Cooper band, guitarist Glen Buxton was the writer of several of hard rock/heavy metal’s most instantly identifiable guitar riffs. Born in Akron, OH, on November 11, 1947, Buxton grew up in Arizona, befriending high school tracksters Vincent Furnier and Dennis Dunaway, who invited Buxton to join up in a spoof band (the Earwigs) they put together for a school show. After receiving a favorable reception, the group changed its name to the Spiders, before relocating to California (with second guitarist Michael Bruce and eventually, drummer Neal Smith). First playing shows as the Nazz, the quintet changed its name to Alice Cooper, with Furnier eventually taking the band’s name as his own. The newly christened group specialized in a highly theatrical and macabre stage show, which took awhile to catch on with rock’s audience.

Although they befriended other bands in California (namely, early supporter Jim Morrison) and issued a pair of psychedelic albums that were musically comparable to early Pink Floyd, neither 1969’s Pretties for You and 1970’s Easy Action faired well. After a move to Detroit, the Alice Cooper group toughened up its sound on breakthrough albums from 1971 (Love It to Death and Killer) as Buxton’s metallic guitar riffs helped fuel such rough and ready compositions as “I’m Eighteen,” “Is It My Body,” “Be My Lover,” and “Under My Wheels.”

But Buxton’s finest moment with Cooper was yet to come — arriving on 1972’s School’s Out. The album was a massive hit, as its classic anthemic title track featured one of hard rock’s best all-time riffs, courtesy of Buxton. Just as the group was hitting its stride, a lifelong alcohol dependency began to affect Buxton’s performance, which hindered his input on arguably Alice Cooper’s finest hour, 1973’s Billion Dollar Babies (it’s been speculated that Buxton’s guitar wasn’t even audible on the ensuing tour, as his parts were supplemented by touring guitarist Mick Mashbir). Despite the Alice Cooper band’s standing as one of the world’s most popular rock bands, the quintet split after only one more release, Muscle of Love.

Little was heard musically from Buxton after the group’s split, aside from appearing at an all-star 1978 benefit for Dead Boys drummer Bobby Blitz at New York’s CBGB’s. In the mid-’80s, Buxton lent some guitar work to Blue Öyster Cult guitarist/singer Buck Dharma’s 1982 solo album, Flat Out, and formed the original group Virgin (unfortunately, the only existing recording of the band is the 1985 bootleg Live at the Mason Jar). In 1997, Buxton was reunited with his former Alice Cooper bandmates (sans Cooper himself), on Antbee’s Lunar Music, and on October 10 of the same year, reunited on-stage with Smith and Bruce for the first time since Cooper’s breakup at the Area 51 club in Houston, TX. While longtime fans speculated that all this activity would eventually lead to a full-on original Alice Cooper band reunion, all hopes were extinguished barely a week later on October 18, when Buxton, 49, died in an Iowa hospital due to complications brought on by pneumonia. Buxton’s gravestone features an adaptation of the album artwork for Cooper’s School’s Out album, as well as a musical transcription of his world famous guitar riff for the album’s aforementioned title track.

********************

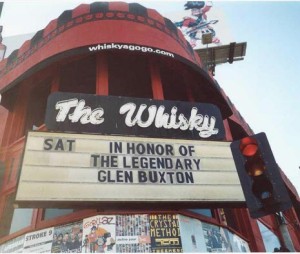

Editor’s note: This article originally ran in the Arizona Republic in October 1999, when a Valley tribute to Glen Buxton, a late member of Alice Cooper’s original band, was staged. Cooper and that band will be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame on Monday, March 14.

Reach the reporter at larry.rodgers@arizonarepublic.com

Glen Buxton never really had a chance.

Once the wisecracking loner from Phoenix’s Cortez High School was thrust into the no-holds-barred world of rock-and-roll stardom, his fate was sealed.

A founding member of the Alice Cooper group, Buxton was cursed with a double whammy: a penchant for alcohol, cigarettes and switchblades as well as a disdain for authority figures – including the doctors who struggled to keep him alive.

But he was blessed with a magnetic personality and musical talent that helped produce rock classics such as “I’m Eighteen,” “Under My Wheels,” “No More Mister Nice Guy” and “Billion Dollar Babies.”

Half a lifetime after he fired off some of rock’s most memorable guitar riffs – including the opening to “School’s Out,” which now graces his tombstone – Buxton’s battered body wore out.

Pneumonia was the official cause of death, but those close to Buxton agree that the satin-clad guitar hero who once played to stadiums of 60,000 fans had been felled by the demons of drink and drugs, along with a stubborn streak that made him ignore his doctors’ warnings.

“There would be no Alice Cooper without Glen,” says Paradise Valley resident Cooper, who found early success with Buxton and Michael Bruce (guitar), Dennis Dunaway (bass) and Neal Smith (drums).

“When it came to the music, we’d look at Glen and say, ‘Glen, what do we do here?’ . . . I think that people didn’t realize that about him – he was our main musical force in the beginning.”

The beginning was at Cortez High in northwest Phoenix in the mid-1960s. Buxton, Dunaway and Cooper, then known as Vincent Furnier, met through the school newspaper.

“Glen was in photography class and I was in the journalism class,” recalls Dunaway, who now lives in Connecticut. “As the sports editor . . . when I’d do a story, I’d call on Glen to go take the picture for the paper.”

When the future Alice and Dunaway decided to do a Beatles spoof for a talent show, they turned to Buxton.

“Glen was the only person we knew who played guitar,” Dunaway recalls. “Since none of us played any instruments, we asked him if he would play guitar while we mimed and pretended.

“Everybody in the audience thought it was a joke – ha ha – but we were thinking, ‘Wow, this is great. Let’s do it some more.’ ”

And did those guys ever do it some more – and more and more.

With Buxton helping Dunaway and later addition Bruce with their musical chops – first as the Earwigs, then the Spiders and the Nazz – the group honed its cutting-edge act at clubs such as the V.I.P., the Dunes and the Beau Brummell.

Some of those bars were a bit on the rough side, recalls Smith, a Camelback High graduate who joined up in 1967.

“Glen and I used to get in fights in Arizona all the time,” he says. “They just thought we were two long-haired hippies. But they didn’t realize we were two punks from Akron.”

A Young Rebel

Buxton was born in Ohio but spent his teenage years in Arizona.

His sister, Janice Davison, recalls her brother as a “normal rebellious teenage kid – he didn’t want to mow the lawn and do the chores.”

“He wasn’t that interested in school. He didn’t like to study, didn’t like the authority. . . .

“He got glasses freshman year and just hated them. After the band started playing, he would never wear them.”

Although his mother nagged him to attend Glendale Community College, Buxton’s parents were supportive of his musical career.

“We had a close family,” says Davison, adding that she and her parents saw Alice Cooper perform several times.

Asked how her family reacted to the staged hangings and beheadings of Cooper, the hatchet attacks on dolls and other shock-rock mayhem that brought the band notoriety, Davison replies, “We all just laughed.”

However, life was hardly a laugh for Buxton after the Alice Cooper group gained national popularity in the early ’70s, with the albums “Love It to Death,” “Killer” and the monster hit “School’s Out.”

The success brought money and adoring females, but it also brought pressure to continue recording and performing to fuel a machine that included a private jet, an expensive stage set and a growing entourage.

“We were either touring or recording or writing all the time, every single day from 1967, when I joined the band, till when the band stopped playing in ’74 and ’75,” drummer Smith recalls.

The constant travel and pursuit by rabid fans was a thrill initially but a burden later.

“It’s an assault on your ability to keep your wits about you,” bassist Dunaway says.

With that kind of pressure, the band members turned to alcohol and drugs in varying degrees to relax.

“It was the party that never ended,” Smith says. “We weren’t really sleeping as much as passing out and getting up and doing it all over again.”

Buxton, who had developed a fondness for alcohol in high school, carried the partying to extremes as the group stormed through tours such as “Billion Dollar Babies” (“Seventy cities in ninety days,”guitarist Bruce sighs).

“I always said Glen made (Rolling Stone) Keith Richards look like a Boy Scout,” Smith says. “Glen just partied hard all the time . . . and I guess he became more of a rock and roll casualty than anybody else in the group.”

Asked to explain why Buxton pushed himself to the point of abuse, Cooper – who quit drinking in 1983 – replies, “Glen and I were drinking buddies. I spent more time drinking than anything else.

“I don’t know why I became an alcoholic, let alone I couldn’t tell you why Glen drank so much. . . . It was just something that happened when you spent that much time on the road.

“I don’t think it was a personality flaw or anything, because Glen never missed a show. . . . And none of us – we never missed a show because of abuse.”

Eerie Guitar Work

In the relative sanity of the recording studio, Buxton’s eclectic guitar work was a key ingredient of the Cooper band’s sound – an eerie mix of hard rock, twisted ballads and larger productions such as “Elected,” “Gutter Cats vs. The Jets” and “Muscle of Love.”

“‘Glen was not a songwriter,” Cooper says. “He would write riffs, though. . . . They would show up on the album and even great guitar players would say, ‘What is that line? It’s so weird, but it’s catchy.’

“Mike (Bruce) was much more into chord structure. So, Glen was always sort of our icing on the cake. . . . When everything was done, we’d bring Glen in to put on the little details and oddities.”

In Smith’s view, “School’s Out” “was Glen’s album – he played all the lead guitar.”

But as Cooper and the others sought a broader sound in the next two discs, Buxton seemed to resist.

“Because of the problems that Glen was having with the demons of rock and roll at that particular time – really, “Billion Dollar Babies” and “Muscle of Love,” Glen didn’t really play on the (latter) album – by hook or by crook, the albums had to be put out,” Smith says.

At that point, the band brought in other guitarists to fill the gaps and augment its sound, including Camelback High School alumnus Mick Mashbir, who also toured with the group in its later days.

To complicate matters at this point, Buxton was hospitalized for two weeks with pancreatitis and was told to clean up his act.

“The doctor told him, ‘I opened up your stomach and I was thoroughly disgusted!’ ” Davison recalls with a chuckle.

“He was in the hospital, and we sent tapes out to him so we could learn the (‘Billion Dollar Babies’) material,” Bruce says. “When he came back, he hadn’t spent any time learning the material. At that point, we brought in Mick Mashbir and (keyboardist) Bob Dolin.

“After that, Glen never seemed to catch up – a day late and a dollar short, sort of.”

Talk with the former members of this close-knit band (band members lived under the same roof in locales from California to Detroit to Connecticut throughout their run at the top of the charts) and you’ll hear differing versions of their breakup.

Cooper says there was disagreement over how much money to sink back into the stage show. Smith says the members simply took a year off for solo projects and never reunited.

However, Bruce says a confrontation with Buxton over his substance abuse – which included one incident in which Buxton pulled his ever-present switchblade on the group’s tour manager, according to Bruce – may have sown the seeds of the breakup.

“Neal and Alice and I went over to Glen’s house and said, ‘Listen, you need to get help . . . we’re gonna put you on a temporary leave without pay,’ ” Bruce recalls. “He (Buxton) goes, ‘No, I’m not gonna do it.’

“Then we said, ‘OK, we’re doing solo projects.’ . . . When it came time to get back together, Alice didn’t want to because of the situation with Glen.”

When the band’s end officially came, in 1975, Buxton was living in Greenwich, Conn.

He chose not to record a solo project, instead spending his time buying antiques and going to yard sales, his sister says.

Left on his own to handle his finances, Buxton got into money trouble. When he failed to pay taxes on proceeds from a mutual fund set up and later sold by the band, the IRS came calling. By 1979, “he had lost his house,” Davison says. “Then he went to an apartment in New York City.”

He played in a band called Shrapnel and frequented punk hot spot CBGB’s. Later, Davison says, “he lived with friends (in New York). The money was going.”

His parents talked Buxton into moving back to the Valley, and he lived at their house in the early ’80s.

At that point, according to Davison, Buxton had “a guitar – that’s about it.”

Moving Full Circle

Davison hooked her brother up with an old high-school pal and they formed Virgin, which took Buxton full circle – back to playing radio hits, as well as some of his songs, in local bars such as the Mason Jar.

He also had his first day job in years, soldering transistors for Goodyear Aerospace for five or six years.

To his good fortune, a rock memorabilia dealer found him with the help of Bruce, who remains a working musician. The dealer, John Stevenson, saw the tough time Buxton was having and invited him to move to an Iowa farm.

Buxton worked in a factory near Clarion, but more important, he met a woman, Laurie Miller, who “was great,” Davison says.

“I thought she was perfect – a geriatric nurse who could take care of Glen!” Davison chuckles.

By this time, Buxton also was suffering from a bleeding ulcer and liver problems.

“He wouldn’t go to the doctor when he should,” Davison recalls. “He hated doctors.”

Buxton enjoyed a taste of his glory days when he reunited with Smith and Dunaway for some Houston appearances in the fall of 1997.

After he returned from Houston, Buxton, 49, remarked to his sister that he had a pain in his side, possibly from lifting luggage.

“I’m gonna have to go to the bone crusher,” he told her.

Later that night, trouble arose.

“He felt clammy, his pulse was . . . not steady,” Davison says. “She (Miller) called the ambulance and they went to the closest hospital. He perked up and was joking with the nurses, being Glen, being funny.

“He said, ‘Well, I’m kind of tired. I think I’ll rest for a minute.’ He looked at her, said, ‘I love you,’ and that was it.”

Buxton never woke from his slumber. An autopsy found viral pneumonia as the cause of his death on Oct. 19, 1997.

But those close to him agree that life in rock and roll’s fast lane, mixed with a stubborn streak, sped his demise.

“There was never a way of me saying, ‘Glen, you gotta slow down,’ because that was like me talking to the wall,” Cooper says. “He would look at me and just laugh and say, ‘Right.’

“That was him, and nobody could change him. He was Glen, and that’s why we loved him.”

Phoenix New Times: October 30, 1997

Unsung Guitar Hero

Glen Buxton played a crucial role in rock history but how many people knew about it?

It was a Friday night and Glen Buxton was jumping up and down with excitement as watched boxing on TV. The only indication that anything was wrong was a pain in his side, which he mentioned to his younger sister Janice Davison over the phone that night He thought he’d strained his back, carrying luggage on a recent trip to Houston “He said, ‘I’m going to have to see the bone crusher tomorrow; my back’s hurting me,'” Davison recalls.

By the next day, Saturday, October 18, the 49-year old guitarist had been overtaken by pneumonia, and he died quickly in his adopted hometown of Clarion, Iowa.

There are many sad elements to the Glen Buxton story, but maybe the biggest one is that many people in the valley have never heard of him. Though he grew up in Phoenix, attended Cortez High School and. played guitar for the most successful rock band ever to come out of these parts, he’s a victim of rock’s strangest injustice.

You see, Buxton played in the original Alice Cooper group, when Alice Cooper was the name of a band, and its singer still went by his given name of Vince Furnier. When the band agreed that Furnier should himself assume the name of Alice Cooper, as a way of answering that persistent audience question, “Where’s Alice?,” confusion reigned forever in the minds of rock fan’s.

It’s hard to think of a comparable situation, unless you count the case of dimwitted fans who actually started referring to Deborah Harry as “Blondie.” when Lou Reed’s career is assessed, fans can point to clear demarcation lines. He played with the Velvet Under-ground from 1965-70, and he’s been a solo artist from 1971 to the present. Yet, because Furnier/Cooper co-opted his band’s name, so dominated its public image, many of his fans believe he’s been a solo artist for 29 years, albeit with a variety of backing bands. Few realize that he was a member of a full-fledged band for six years and a solo artist for the next 23. Not so coincidentally, Furnier/Cooper lost much of his rock ‘n’ roll grit when he sacked the band in 1974.

Buxton met Furnier and bassist Dennis Dunaway when they worked together at the Cortex High School newspaper, the Tipsheet. Buxton was the photographer, Furnier was the editor. They went on to form the Spiders, one of the wildest rock bands the Valley had ever seen, and after a brief period as the Nazz, they settled on Alice Cooper as a band name.

Buxton wasn’t a full-blown songwriter in the sense that guitarist Michael Buxton and Furnier were, but he came up with the killer guitar rifts that heralded the arrival of their great anthems: “I’m Eighteen,” “School’s Out” and “Elected.” His wicked guitar part for “I’m Eighteen” alone makes him Hall of Fame material.

In his controversial band biography, No More Mr. Nice Guy which Furnier/Cooper has dismissed as a work of fiction-Bruce blames Buxton’s deepening drinking problems and sense of detachment for Coopers decision to go solo. Sadly, alcohol continued to play havoc with Buxton’s life until the end.

“He would quit for a while and then he’d start up again, or he’d say, “I’ll just drink beer,”‘ Davison says. “But he wasn’t supposed to drink after he’d had problems way back in the 70’s.”

Buxton tried putting other bands together, like a short-lived New York outfit called Shrapnel. Davison says that to the very end, “he always had a guitar in his hands.” In the mid 80’s he returned to Phoenix and played in a band called Virgin. Though his return to the stage was welcomed, old fans winced a bit to see one of rock’s great underrated guitarists covering Yes’ “Owner of a Lonely Heart” and various old Alice Cooper Hits.

But what does a great guitarist do after playing to exultant stadium crowds by the age of 22, then seeing his lifeblood taken away by the time he’s 27? Just being a guitarist in a bar band, which was what he’d started doing, didn’t seem adequate any-more. But unlike his ex-bandmates, Buxton had a tough time just making a living after the band broke up.

“1 just found out what happened with the money,” Davison says; “when they were Alice Cooper, Inc., they had an account, and when the corporation broke up, they gave the money to the guys. And you have to pay taxes on it. And what did Glen do? He spent it of course. So he had tax problems after that. He was living in Connecticut at the time and had to sell his house.”

To get by, Buxton worked sporadically at a variety of jobs, including a stint at Goodyear in the 80’s, where his ax was a soldering gun. After moving to Iowa, he worked for a spell in a factory, overseeing a machine that stuffed Publisher’s Clearing-house letters in envelopes.

Ironically, Buxton’s life had taken a positive turn in the past two months. In August he caught a Furnier/Cooper show in St Paul, Minnesota, and the two old friends spent an hour talking up the old times. In early October, he reunited with old Alice Cooper bandmates Michael Bruce and drummer Neal Smith for a series of autograph shows and live performances in Houston. Davison says her brother “had a ball” reuniting with his old friends, adding that he showed his forgiving nature by playing again with Bruce, despite Bruce’s unflattering portrait of Buxton in No More Mr. Nice Guy.

What’s most important now is that Cooper fans recognize Buxton for the crucial role he played in one of the few great bands of rock’s most depressing era, the early ’70s.

His old Cortez High School comrade Vince Furnier, known to the world as Alice Cooper, has done his part to set the record straight. In a statement released last week, Cooper said the following: “I grew up with Glen, started the band with him and he was one of my best friends. I think I laughed more with him than anyone else. He was an underrated and influential guitarist, a genuine rock ‘n’ roll rebel. Wherever he is now, I’m sure that there’s a guitar, a cigarette and a switchblade nearby.”